Professor Emeritus, Keio University /

Chairman, Institute for Urban Strategies, The Mori Memorial Foundation /

President, Academyhills

At this year’s Urban Strategy Session, we have already hosted a total of three presentations and engaged in discussions about Tokyo’s identity. Today’s proceedings will be broken into three parts—relay talks from our presenters, a special address, and a panel discussion—during which we will engage in constructive debate about an ideal future for Tokyo, with reference to what we have heard thus far. To begin today’s session, let us first hear from a researcher of the Mori Memorial Foundation (MMF) about the history of Tokyo’s development and what makes it the city that it is today.

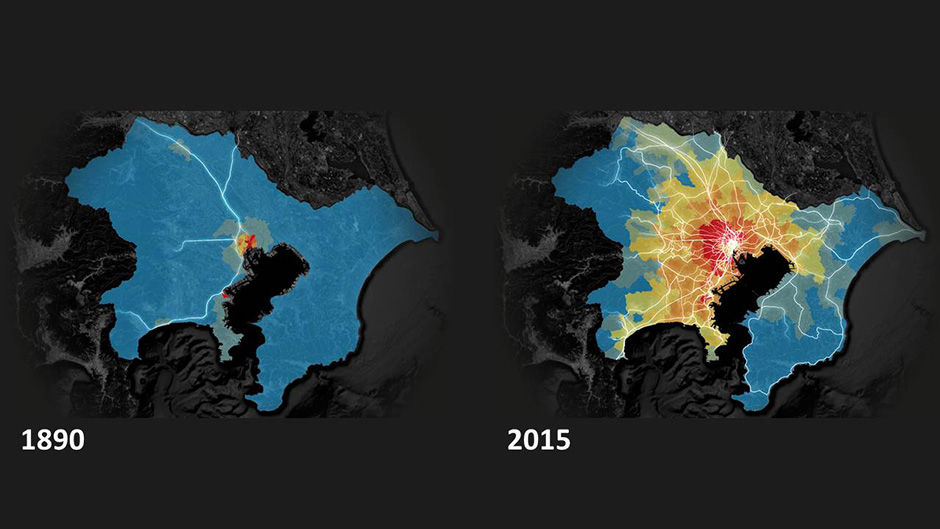

We investigated the urban growth history of Tokyo from the perspective of population density and railway network from 1890 to 2015. A few years after the Meiji Restoration in 1867, a railway running between Shinbashi and Yokohama was opened. At that time, resident populations were only found within the confines of the current Yamanote Line and in Yokohama. By around 1910, train lines were beginning to stretch in all directions and as a result, the population started to increase in some cities such as Choshi, Sakura, Chiba, Omiya, Kawagoe, Kumagaya, Hachioji, and Yokosuka. By 1930, the Tokyo and Yokohama areas began to mesh together and by 1950 the urban sprawl had spread as far as Chiba-city and Yokosuka, as well as Hiratsuka in Kanagawa Prefecture. Later, by 1980, the development of Tama New Town extended Tokyo’s reach out towards Hachioji. A comparison with today’s population density distribution shows just how fast Tokyo has grown in only 125 years from 1890 through 2015.

In order to identify what makes Tokyo the city it is today following such rapid development, we performed two types of analyses—one based on photos and the other using keywords. For the former, we categorized and analyzed photos that the audiences of the three preliminary seminars thought represented Tokyo the most. The overwhelming choice of most participants was the physical landmark of Tokyo Tower. Other photos chosen by many were those related to the city’s infrastructure, such as Tokyo’s subways or the multilayered urban landscape of the metropolitan expressway. Other photos included things of Japanese design, as well as food, temples and shrines, festivals, and alleyways. Among the collection of photos that strikingly depict the old and new of Tokyo, many of them show fireworks and the Tokyo Skytree, or Zojoji Temple and Tokyo Tower, or other contrasting scenes like a torii shrine gate nestled among modern buildings.

For our analysis of Tokyo based on keywords, we collected keywords put forward by the audiences at the presentations and today’s session. The most common response was “Tokyo Tower.” Other keywords put forth included “high-rise buildings,” “crowded,” “clean streets,” “convenience,” “clean,” and “Japan.” In the Mori Memorial Foundation’s City Perception Survey conducted on foreign visitors in the past, the most common keyword used to describe Tokyo was “crowded.” Our research indicates that the images Tokyoites have of their city and the images that foreign visitors possess are both similar and different.

Much like “infrastructure” and “monument,” the word “identity,” the topic of our session today, is quite difficult to translate into Japanese. Identity can be applied to various levels, such as the individual, organizations, cities or nations. With respect to cities, identity lies hidden in history and is shaped over the passage of time. In the case of Tokyo, we must take into consideration the transformation of its history, from the Edo period, to modern times, and finally to the present.

Edo was settled in the Middle Ages, expanded as a castle town, and then grew into a great city in the closing days of the Tokugawa shogunate, and symbolic places emerged during those different periods. In the Meiji period, the city transformed from the old castle town of Edo into the modern city of Tokyo. The biggest change was Edo Castle becoming the Tokyo Imperial Palace. Elsewhere, the land around Edo Castle where samurai residences once stood was utilized for government offices and military purposes. The temples around the outside of the castle were transformed into five parks, including Shiba Park, Asakusa Park, and Ueno Park. In this way, Tokyo was transformed into a modern city but inherited the urban structure of Edo.

The biggest changes to Tokyo in the post-war period came in the 1960s. In celebration of high economic growth, the predominate thinking of the time in the field of architecture was that urban design is the same thing as city design. During this period, large-scale development plans began across the country, and as they progressed a number of culturally important buildings were demolished and lost forever. Recently steps have been taken to rebuild them.

Looking at current-day Tokyo, I think some parts of this integrated city are gradually breaking away. In other words, Tokyo is increasingly transforming into a set of islands. Places like Nihonbashi, Ginza, Roppongi, Aoyama, and Shibuya demonstrate strong magnetism and each of those areas looks as if it is an islet dotted on the sea. Put another way, Tokyo is like one big archipelago. Tokyo’s identity is certainly multi-faceted and the city itself continues to morph into a city that binds together multiple identities. In what way should Tokyo be shaped as a whole going forward will likely be a major topic of discussion for urban planning in the future? Areas linking these islets together could be roads or open spaces. In other words, we need ideas on how to connect this “Tokyo archipelago.” And more than anything else, I hope that sturdy buildings will be erected and become ingrained into Tokyo’s identity.

My job is to show people the traces of history that generally remain hidden throughout Tokyo. I think most people consider Tokyo to be a modern and futuristic city, but when you actually walk around and investigate the narrow side streets between the high rises, you can uncover a history stretching back 400 years to the start of Ieyasu Tokugawa’s shogunate.

As an example, nearby the west exit of Iidabashi Station there is a great stone wall—this is where the Ushigome Gate to the outer moat of Edo Castle once stood. The stone wall is a relic of the giant gate tower. There is another stone on the opposite side next to the police box which still bears the engraving Awa no kami, the court title of the daimyo (feudal lord) Hachisuka Tadateru from the Tokushima domain. He led the construction of the gate tower in Edo’s early days. Tokyo is actually littered with similar vestiges of Edo Castle’s history.

On the street in Iwamotocho near Akihabara there is a mooring stone that was used in the Edo period to tie boats up to the shore of the Kanda River. The river was utilized as Edo’s main distribution and transportation artery, which is why a mooring stone was placed there. Even after the town was transformed, the stone was left standing. The stone now bespeaks the history of the area, which once flourished as the center of water transportation for Edo. Many of these interesting artifacts still remain in Tokyo.

The open water you can see from the window when travelling on the Sobu Line is the outer moat of Edo Castle. When the Sobu Line was being built in the Meiji period, the edge of the outer moat was filled in to make room for the tracks to run between Yotsuya and Asakusabashi. The metropolitan expressway that was built immediately before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics was also completed on time because the canals from the Edo period were reclaimed, enabling the construction of elevated roads.

If you look at an aerial photograph taken above Ginza in the direction of the palace, you can see that many large buildings are concentrated in the area to the left of the railway. This area was part of Edo Castle during the Edo period. Many daimyo mansions were located within the Edo Castle precinct but the land they stood on was used to build government and office buildings in the Meiji period. In contrast, Ginza had been a commercial district since the days of Edo through to the Meiji and Taisho periods and stores built on small plots of land have remained in that area ever since. This is why aerial photographs show such a high concentration of buildings there. The area extending from Ginza up to Kyobashi and Nihonbashi was designated a commercial district by Ieyasu Tokugawa.

Despite Tokyo being a veritable forest of high-rise buildings, the remnants and traces of history have yet to disappear from its streets. I think the layering of this history is what defines Tokyo today. By learning how the streets came to be as they are now, I think we can gain a clearer picture on the direction of urban planning in the future.

Personally, I would like to see the main tower of Edo Castle rebuilt in the future. This plan would carry both outward-looking and inward-looking significance. From an outward-looking perspective, I think its wooden construction would be a crystallization of the exceptional level of Japanese technology and form the crux of Tokyo’s tourism strategy. From an inward-looking standpoint, I think people living in castle towns in regional areas understand the sense of pride of being raised in a town with a castle to look up at, which is something that should be shared with the people of Tokyo. This is the kind of building that Tokyo is missing, so I really hope that one day it can be restored.

Creating a place that in some way leaves an indelible impression on the guests was at the forefront of our minds when we designed Hoshinoya Karuizawa, the first of the Hoshinoya series of resorts. As a result, the idea of a village in a valley was born. For Hoshinoya Kyoto, we had the opportunity to think about the role of Japanese-style guest rooms. Currently I think there are not too many people who still have Japanese rooms with tatami flooring in their homes, but we gave a lot of thought to how we could convey to these people, as well as foreign visitors, a style of living centered on Japanese rooms. Moreover, on Taketomi Island in the Yaeyama archipelago, a roughly one-hour flight from Okinawa Island, traditional Okinawan houses remain and entire villages have been designated as Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings by the Japanese government. At the Hoshinoya Taketomi resort we aimed to create a new village on that small island and in doing so, examined ways to pay respect to the local environment.

In advancing these projects, we started to consider the passing down of materials and skills to future generations. When I visited Kyoto, I frequently saw kyo karakami (traditional paper used to cover sliding doors in places like temples, but only one surishi (craftsman specializing in printing) that can make this kind of special paper remained in Kyoto at that time. The nurturing of the younger generation to become surishi is currently being encouraged, but the acquisition of these artisanal skills takes many years. The main reason why the number of kyo karakami craftsmen has declined is that the paper is no longer used for sliding screens. With the emergence of new materials for sliding screens, the use of expensive kyo karakami will gradually die out. The techniques that should be preserved for the future will only disappear if they are no longer used.

As for Japanese rooms, their evolution likely came to a halt sometime after World War II because of restrictive definitions on style. But if we trace back their history, they first appeared in the Heian period in the form of tatami mats laid down in rooms with wooden floors and have since evolved through the ages. We too, as modern-day people, must revisit this evolution. For Hoshinoya Kyoto, we came up with new ways of relaxing on tatami mats, such as developing sofas that let guests sit on the tatami. Instead of trying to preserve style, we aimed to develop something new. What precedes us has no shape and goes unseen. We consider what kind of experiences we would like people to have and then think about giving them shape and substance.

For Hoshinoya Tokyo in Otemachi, we ultimately decided on the ryokan (Japanese inn) theme because Tokyo lacks such a prominent establishment. When we were thinking about what kind of ryokan we should create, rather than just building a hotel with lots of Japanese rooms, we came up with the idea of having guests take off their shoes. On the first floor we designed an entrance area with a five-meter high ceiling and placed the shoe shelf within reach on the left-hand side. When guests come down from their rooms, the hotel staff appear like magic to take out their shoes. This provides guests with an old-ryokan experience where a doorman would take care of the shoes. At the same time, by having guests relax with their shoes off, they learn how people in Japan relax and start to think about the whole process. While the size and layout of the guest rooms are pretty much on par with those of the global hotel chains, the major difference is that they are covered with tatami. Even though it may be difficult to preserve the old style of Japanese rooms, for a culture where people take their shoes off inside, we realized that tatami would be essential. We want the guests to understand that if one is to walk barefoot without slippers, then tatami is the most comfortable material for Japanese people. If we are to create a new identity for Tokyo, I think it is our job to think about how we can strengthen the city’s weaknesses, make it more interesting, and come up with ways to promote Japan even further by giving it shape and substance.

The background to today’s topic, Tokyo’s Identity: An ideal future for Tokyo generated by creativity and continuity of time, can be traced back to last year’s ICF session. Based on the topic of Tokyo in 2035, we painted a picture of what Tokyo’s future might look like in 15 to 20 years from now as technology evolves and values change. As part of our discussions, we reached the conclusion that Tokyo’s future would be “sophisticated and something edgy.” That is, we concluded that while Tokyo should be sophisticated, a simultaneous edginess was also required. That was the beginning of this year’s topic. So, what exactly is an “edgy Tokyo?” As mentioned in the introduction, Tokyo grew rapidly and transformed into the world’s largest metropolitan area. The origins of that development lie in the 260 year-long Edo period.

Development is ongoing in various districts across Tokyo, driven by a major developer in each area. The four areas we heard about in the presentations given earlier were the Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho area, the Nihonbashi area, the greater Shibuya area, and the Roppongi and Toranomon area.

Nakadori, an avenue in the Marunouchi district, used to be a typical office building area, devoid of life both at night and on weekends, but it underwent a radical transformation after 20 years. Various initiatives are now implemented for this precinct, including the temporary closure of vehicle access to create a pedestrian mall. This was actually the first district where area management was implemented and such area management activities and the establishment of an ordinance to promote the creation of stylish streetscapes in Tokyo have made the area more appealing. Thanks to these area management activities, the precincts of Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho, where some of Japan’s most well-known major corporations have their head offices, are no longer just business districts—they now serve as the nucleus of Tokyo’s future. Mitsubishi Estate aims to turn this area into a place where people and companies can realize their potential and evolve.

Nihonbashi during the Edo period was the center of economy, finance, commerce, distribution, and culture. At that time, this merchant town accounted for only around 20% of Edo in terms of area, but more than half of the city’s population was crammed in there. In today’s language, we would say Nihonbashi had hybrid functionality because people lived and did business there. Being bold enough to undertake development in an area with such historical foundations is one attribute of Mitsui Fudosan. The company is forging ahead with an ambitious plan to replicate the streets of Edo behind the COREDO shopping complex and bring back and incorporate the old shrines into its modern urban design. The specific themes of its plan include community cohesion and creation of new commerce, the revival of water features, and the inheritance of the sophisticated mentality of Edo merchants. If the elevated metropolitan expressway that runs over Nihonbashi can be taken down in the future, many more people will likely flock to the area. Nihonbashi is characterized by diversity, perseverance, innovation, and human interaction.

Shibuya was an area on the outskirts of Edo in those times, but it now occupies a corner of inner-city Tokyo. As a suburb, it developed around the terminal of the Toyoko Line, which first commenced services in 1934. But what transformed this town was the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. During this time, NHK moved its headquarters from Marunouchi to Shibuya and the area became a hub for the information industry. Nowadays, Shibuya is not just a station on a railway line—it is a place where people from all over the world come to visit. 100,000 people habitually gather there to usher in the new year, and the famed pedestrian scramble crossing and the area in front of classic Shibuya 109 building are known the world over as iconic symbols of Shibuya. Plans are in motion to transform the area—six new buildings will be constructed over the next 10 years or so and the station will receive a complete makeover. The local terminal station town of yesteryear is at last ready to vault onto the world stage. Meanwhile, the concept of a greater Shibuya refers to the area within a 2.5-kilometer radius extending from Shibuya Station, encompassing precincts such as Daikanyama, Omotesando, Harajuku, and Aoyama.

Lastly, I must mention the area of Toranomon and Roppongi where the Mori Building Company is undertaking development projects. As already mentioned, Tokyo’s key resources were amassed during the Edo period. By the end of the Edo period, this area was overflowing with daimyo mansions of considerable size. Various developments commenced in the Meiji period and transformed the area. Today, urban development is underway that utilizes the features of the area. Being a samurai residential area, it is strikingly different to the merchant district of Nihonbashi. For this reason, urban development methods also differ. Based on its Vertical Garden City concept, Mori Building is employing a vertical approach to urban development and has successfully enriched the town by injecting culture and filling the narrow spaces with greenery. This area lies between Nihonbashi, Marunouchi, and greater Shibuya and if all goes smoothly, each of these different development sites will be interconnected. Just as Professor Ito explained moments ago, Tokyo is transforming into a chain of islands, but the question is how do we link up each of these areas that have surfaced on their own? I think this will be key for Tokyo in the future.

The primary reason why the Japanese government is pouring so much effort into its tourism strategy is the problem of population decline. If we take a look at future projections of working-age populations around the world, Japan’s working population is expected to shrink by 32.64 million people between 2015 and 2060. As the UK’s working population is 32.11 million, the amount of people expected to disappear from Japan’s workforce is greater than the total working population supporting the world’s fifth-largest economy— hence the idea of attracting foreign people to Japan to help contribute to the economy. The tourism industry accounts for 10% of global GDP and is now the third mainstay industry of the global economy. The number of foreign visitors to Japan increased from a little more than 10 million in 2013 to 29 million by 2017 and in terms of global tourism revenue ranking, Japan had jumped up to 10th place last year from 26th roughly five years ago. Also, the country’s foreign currency reserves, previously ¥1.0 trillion, have swelled to ¥5.2 trillion as of 2018. In my opinion, these changes have occurred because the government has strengthened its sense of reality and objectivity.

In most cases, people go travelling because there is someone they want to meet, a place they want to visit, something they want to experience, a food they want to eat, a drink they want to drink, or something they want to see. What is most important for tourists around the world is diversity, nature, climate, culture, and dining. The tea ceremony is a wonderful part of Japanese culture, something I myself have taken to enjoying, but of Japan’s population of 127 million people, only three million practice the tea ceremony. Even though Japanese people themselves are not that interested in the tea ceremony, the constant promotion of this cultural aspect to foreign people indicates a lack of objectivity and realism. While people from overseas list Japanese food as the thing they most want to experience when visiting Japan, this choice is most common among first-time visitors—the ratio of tourists on their second visit citing this reason drops considerably. Although Japanese cuisine is constantly and actively being promoted to foreign people, we must instead come up with ways to publicize Tokyo’s appeal as a city where visitors can experience a wide variety of foods.

Furthermore, in addition to the reasons why tourists come here, it is important that we analyze why some choose not to. The secret to a successful tourism strategy is not branding, promotions, advertising, or mascot characters, but the use of investigative analysis to identify the various issues, followed by step-by-step solutions for each and every problem. The dominant approach employed thus far was to promote and inform foreign people about the spiritual nature of Japan and its wonderful culture, but the unmistakable aim of a tourism strategy is to encourage consumption, so the conventional approach does nothing but teach visitors about spirituality, history, and culture. The biggest problem is how we think about value and added value. For example, the mere existence of something, whether it be the Imperial Palace or Zojoji Temple, has value. However, it is essential that we generate something of added value worthy of consumption in order to bring in revenue. In other words, customer experiences that carry high added value.

Owing to steady improvements implemented for visitors to Kyoto’s Nijo Castle, including activities, tourist information boards, and rest spots, the site recently saw the most people pass through its doors since the hosting of Expo 70 in Osaka 47 years ago. Up until now there had been few people who admired the beautiful Japanese garden within its walls, but the serving of breakfast rice porridge to visitors in the garden turned out to be really popular. People are willing to pay ¥3,000 for the chance to enjoy a quiet two hours over breakfast inside historical buildings surrounded by a Japanese garden isolated from the outside world even if they have no real interest in Japanese palaces. By addressing various issues with the proper solutions, the magnificence of a place and the very experience of it can be improved.

One meeting I was recently invited to is the Ueno Night Park Concept Committee. The committee aims to globally promote Ueno as a center of culture. I think the concept itself is great, but the problem is that even buying a concert ticket is difficult unless you are Japanese. There is no point in promoting culture if nothing is being done, including various improvements and multilingual support, to help visitors understand the qualities of each piece in a collection at the local museum or art gallery. There are also very few cafés at Ueno’s cultural facilities. Improving the level of satisfaction of the experience itself is important, which can be achieved by providing places to sit and making other improvements to encourage visitors to stay longer. To sum up, quietly upgrading tourist sites and investing in equipment is key to transforming Tokyo into a tourist city, in my opinion. A marketing slogan alone will not turn Tokyo into a tourist city. The quality of customer experiences is paramount. Given that Tokyo has an abundance of tourist resources, I think the creation of an appealing city from both a domestic and global standpoint is possible if these resources are improved.

In light of the presentations delivered by each of our panelists, during this second-half panel discussion, I would like us to talk about what course of action Tokyo should ultimately take. First of all, I must mention that in the Global Power City Index (GPCI) released today, Tokyo’s score in the Cultural Interaction function was somewhat weak. Despite the increase in tourist numbers, the city is still evaluated poorly for Cultural Interaction. As Professor Ichikawa heads up the research regarding the GPCI, I would like to hear his thoughts about Tokyo’s strengths and weaknesses from a GPCI point of view.

The cities in the GPCI are assessed across six urban functions and in the function of Cultural Interaction there is a significant score gap between Tokyo, ranked third overall in the comprehensive ranking, and the top two cities London and New York. One of the indicators used to assess cultural interaction in the GPCI is called Cultural Interaction Opportunities, but partly because of the impact of earthquakes and war, not many historical assets remain in Tokyo, unlike in Paris and Kyoto. Consequently, the utilization of different resources and facilities are crucial if we are to attract tourists to Tokyo. On top of this, we need to create an identity for Tokyo and identify what it is that is unique to the city. Tokyo lacks the uniqueness from which a descriptive byword might be conjured, such as the “Gay Paree,” “foggy London,” or “the musicals of New York.” Many of Tokyo’s cultural facilities and resources belong to the public sector but in other parts of the world various public facilities are open to the public with their operations often outsourced to the private sector. If Japan can emulate this, then some of the issues that were pointed out just moments ago could be resolved.

While Hakata Port receives more than 300 cruise ships annually, Japan is unable to turn its ports of call into stylish destinations brimming with cafés like the Port of Naples in Italy. This is because Japanese laws designate ports as places for cargo handling, thus preventing the establishment of cafés or other kinds of shops. We must continue to engage in this kind of debate in an appropriate manner.

A few moments ago, Professor Ito spoke about the possibility that a mechanism for linking together Tokyo’s “island chain” could be the catalyst for shaping the city’s identity. In light of the city’s historical background, I would like to hear your opinion about how Tokyo’s identity should be crafted.

I think cities go through a cycle of becoming islands at some stage and then being reunited again. For example, the great ancient city of Heian-kyo was built in what is now the central part of Kyoto, but during the Middle Ages, it split into the two cities of Kamigyo (upper) and Shimogyo (lower). They appeared just like islands in the greater city of Heian-kyo. The two cities were connected by Muromachi Dori, a road that would later become the axis of Kyoto City. In Tokyo, Nihonbashi and Ginza share the same axis, but elsewhere there are only roads devoid of character spreading across the city. I think the very fact that Tokyo is now a chain of islands presents us with an opportunity. The city of Tokyo began with the “island” of Edo Castle before gradually expanding into what we see today—groups of islands in various locations. Linking them all together I think will shape an identity for Tokyo unlike any other city in the world.

Mr. Kuroda has told us there are in fact traces of history hiding in various places throughout the city. It certainly is fascinating to try and find these hidden remnants. What I think is a shame, though, is that place names in Tokyo no longer allude to the vestiges of times gone by. If we could restore some of these old place names, I think it would go a long way in helping tell the story of Tokyo’s history. I would like to hear what Mr. Kuroda thinks.

In the inner-city areas, the former town or street names are displayed on the side of the roads but most people probably fail to notice they are there. While we should learn the history and the local features of an area and endeavor to inform people of such, I think we also need to make some improvements, such as providing Wi-Fi services or information boards. As a city, Tokyo developed in line with economic reasoning, which I think happened without any regard for how it is viewed externally. External points of view must be taken into consideration when considering Tokyo’s identity, and will be vital going forward.

As Ms. Azuma said, the idea of preserving tradition runs deep in Japan. But I also think there exists the notion that value can be increased by adopting contemporary interpretations that suit each time period. Kabuki theater still survives because it has evolved in step with the times. Japan today is focused on preservation by all means necessary and there is a strong tendency for the Agency for Cultural Affairs to inject money into things already preserved. In light of today’s presentations, do you have any suggestions on how we can create an “edgy” Tokyo?

When we think about what it is that we want to preserve and what it is that we should be changing, I think we must ask ourselves whether or not Tokyo is differentiating itself from other cities. Tokyo will never become like New York and it would make no sense if something like Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands was built in Japan. We must look at what Japan can do from a different point of view from other cities. The idea of linking each of Tokyo’s so-called islands was mentioned a few moments ago, but if we are to strive for differentiation, why not emphasize the characteristics of these areas a bit more? For example, by restricting the construction of high-rises in Nihonbashi, or allowing the use of more neon lights in Roppongi. Setting aside the question of whether or not the reconstruction of Edo Castle is feasible, I think that line of thinking is extremely important and the mere consideration of it can give rise to other ideas.

Professor Ichikawa raised the question of how we should go about making Tokyo more “edgy,” but as an expert on urban issues who has continued to observe Tokyo’s evolution, I would like to know what kind of answer he has for this issue.

I think it is crucial that we create a city that appeals to outsiders as well as Japanese people. That said, while I think a city that can secure revenue from tourism is wonderful, whether or not that is in line with Tokyo’s identity is another matter. Paris’ ambience was not created with the specific goal of generating an identity—it was the result of urban planning that aimed to improve public safety, curtail civil commotion, and improve sanitation. The results of those initiatives have become the city’s assets today. In this sense, I feel that the building of a city based on a specific goal at some point in time is likely to yield favorable results further down the line. As we search for and attempt to resuscitate the traditions and history of Tokyo, and by extension, Japan, we might benefit from garnering ideas from foreign people and their differing points of view.

If you were depicting the city of Paris on a poster, you would probably go with the Eiffel Tower and the river Seine. If it was New York, then the Statue of Liberty, representing the spirit of independence and freedom, would be a good choice. Each city has its own story, but what image symbolizes modern-day Tokyo? I would like to hear what Mr. Atkinson thinks.

In the case of New York, if asked whether Broadway was in vogue in the 1980s, you might be aware that that area of the city was extremely dangerous and nobody dared go near it. Owing to the efforts of successive generations of mayors, public safety was improved and the area was cleaned up to roughly how it looks today. London too looked very different a long time ago. How it looks today is the result of continuous upgrades. Big Ben is an iconic landmark of London, but it is not the reason why people visit the UK capital. And in most cases, people do not visit Paris simply because the Eiffel Tower is there. A city is probably better served having a symbol than not having one at all, but not every city is endowed with something. To touch upon Paris again, France’s tourism strategy is actually very interesting and the country has the lowest ratio of visitors to its capital city than any other nation. In other words, many tourists visiting France skip Paris and travel to other regions. And it is not because certain regions of France are characterized by something special. In France the wine is excellent wherever you go and visitors can experience various activities, whether it be at the beach or on the ski fields. As for London, the West End theater district certainly stands out and one of the reasons why is its ticket booths. They have information on all the concerts and productions happening in London and needless to say, you can purchase your tickets there.

I live in Kyoto but the city has more or less become a virtual world. Even though it avoided the ravages of air raids during the war and its shrines and temples remain intact, I feel as if the stores and houses on the streets have all disappeared. Walking around during the year-end and new-year holidays, I notice that not one house or shop had put out a kadomatsu (traditional pine-tree decoration). The residents of Kyoto, who take pride in their 1,200 year-long culture, do not even observe one part of Kyoto culture. Meanwhile, telling foreign visitors to respect Kyoto culture is quite unwarranted. I think the process of being questioned and criticized by foreign tourists about Japan and Tokyo’s identity will serve to strengthen the city and gradually clarify what Tokyo’s identity actually is. As already mentioned, Japanese people surprisingly know little about cultural assets and local history. I think Japanese people can rediscover this knowledge, for example, when a foreign person who knows nothing about Japanese rooms asks a question. So before tackling the question of Tokyo’s identity, I think it is important that people ask themselves whether they identify as being Japanese.

In the GPCI too, even though inbound tourist numbers are up, the extremely low numbers of foreign residents and exchange students in Japan weigh on Tokyo’s ranking. I actually raised the issue of inbound tourism during the days of the Koizumi cabinet, but it was pretty much brushed aside. Having been told that the auto and steel industries are key for Japan and that inbound tourism is not a focus, I kept persisting and the then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Fukuda eventually set up a small research group. That was the beginning of the Visit Japan Campaign. Then a law promoting Japan as a tourist destination was enacted and the government set a goal of increasing foreign tourists from 5-6 million at the time to 10 million. The annual number of tourists to Japan now stands at 28 million. Just as Mr. Atkinson said, it is indeed the steady improvement efforts and the accumulation of such improvements that are important, although I also think the weak yen and relaxation of visa issuance also contributed to these developments.

We must continue to deepen our discussions about Tokyo’s identity, but what I find amazing is that looking at population statistics at the end of the 19th century, the city of Edo was home to one million people. London and Paris at that time had roughly half that, while New York only housed around 30,000. From that time onwards right through to the present day, many more people moved to the area and brought forth a multitude of goods and services. But just as we start forgetting these things, a much greater effort is needed if we are to tell the world about our city. At Japanese universities there are very few so-called tourism faculties—the first ones were established a few decades ago at national universities. Slowly but surely these departments are now statistically analyzing cities and demographics and the results are starting to be used to finally solve problems. Adopting the approach of continually bringing the city’s strong points into play and solving problems is what Tokyo requires going forward. From there on I think we should be able to gain a clearer view of what an “edgy Tokyo” may look like in the future.